Willow Case Study

Introduction

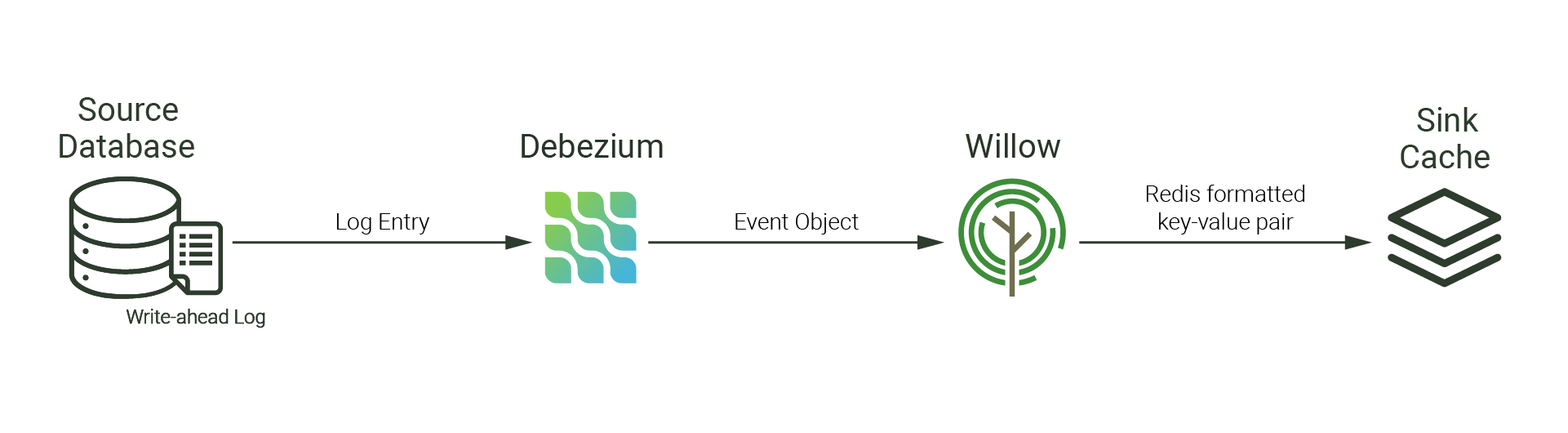

Willow is an open-source, self-hosted framework for building log-based change data capture pipelines that update caches in near real-time based on changes in a database.

Willow abstracts away the complexity of setting up and configuring open source tools like Debezium and Apache Kafka. Utilizing log-based change data capture, Willow non-invasively monitors changes in a user's PostgreSQL database and reflects those row-level changes in a user's Redis cache. Without requiring in-depth technical knowledge and expertise, data pipelines can be created or deleted using Willow's web user interface, simplifying setup and teardown.

This case study provides background on caching and its tradeoffs, explains change data capture, and discusses why developers would use it to keep a cache consistent. Next, Willow's implementation and architecture are explored, and challenges encountered when creating Willow and how these were addressed is explained. Finally, Willow's roadmap for the future is outlined.

Background

General Problem Domain

A web application's response time significantly influences user experience and company profitability. An Amazon study found that every 100ms of latency dropped sales by 1%. Google's research found that a 100ms improvement in mobile site speeds increased how many visitors made purchases by up to 10%. Web applications are growing increasingly complex and distributed, forcing developers to find ways to improve application speed and response time.

One source of slowdown is an application's database. Database queries can become a limiting factor for an application’s response time for various reasons, including when multiple applications are simultaneously accessing the database or when unoptimized queries block other queries from being executed. A common way to increase read response times is to utilize a cache.

Caching

Caching is a strategy to improve web application performance by taking demand off of source databases and providing speedy access to data. With caching, frequently accessed data is stored in a temporary location. This is usually an in-memory form of storage, which means data can be accessed faster than persistent, disk-based storage. By utilizing caching, an application checks the cache for data before requesting it from the database. This can reduce read demands on the source, taking pressure off of the database and increasing the speed of the application overall.

However, there are tradeoffs when using a cache. One major challenge is keeping data in the cache up-to-date and consistent with the source of truth. This issue is known as cache consistency.

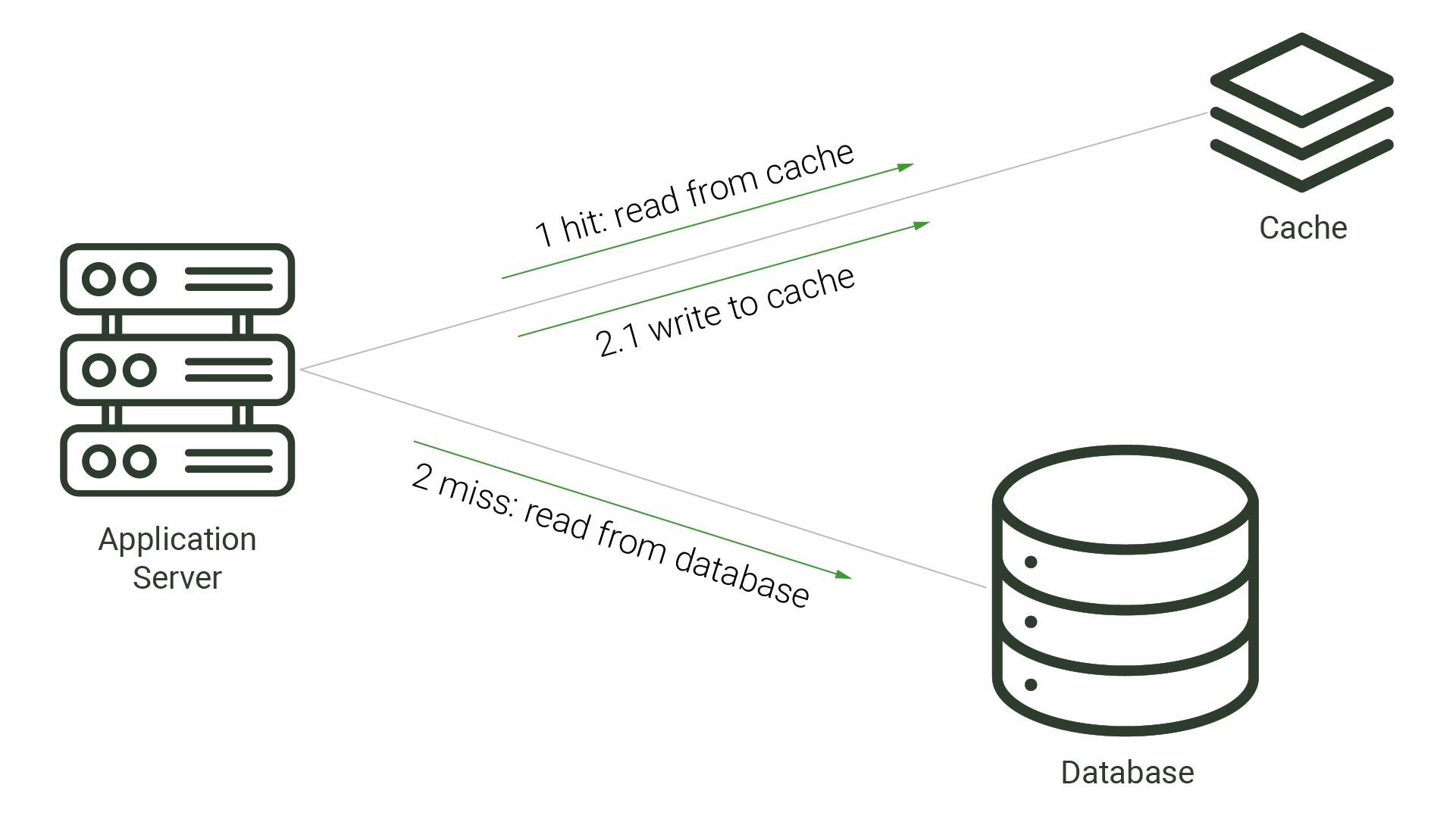

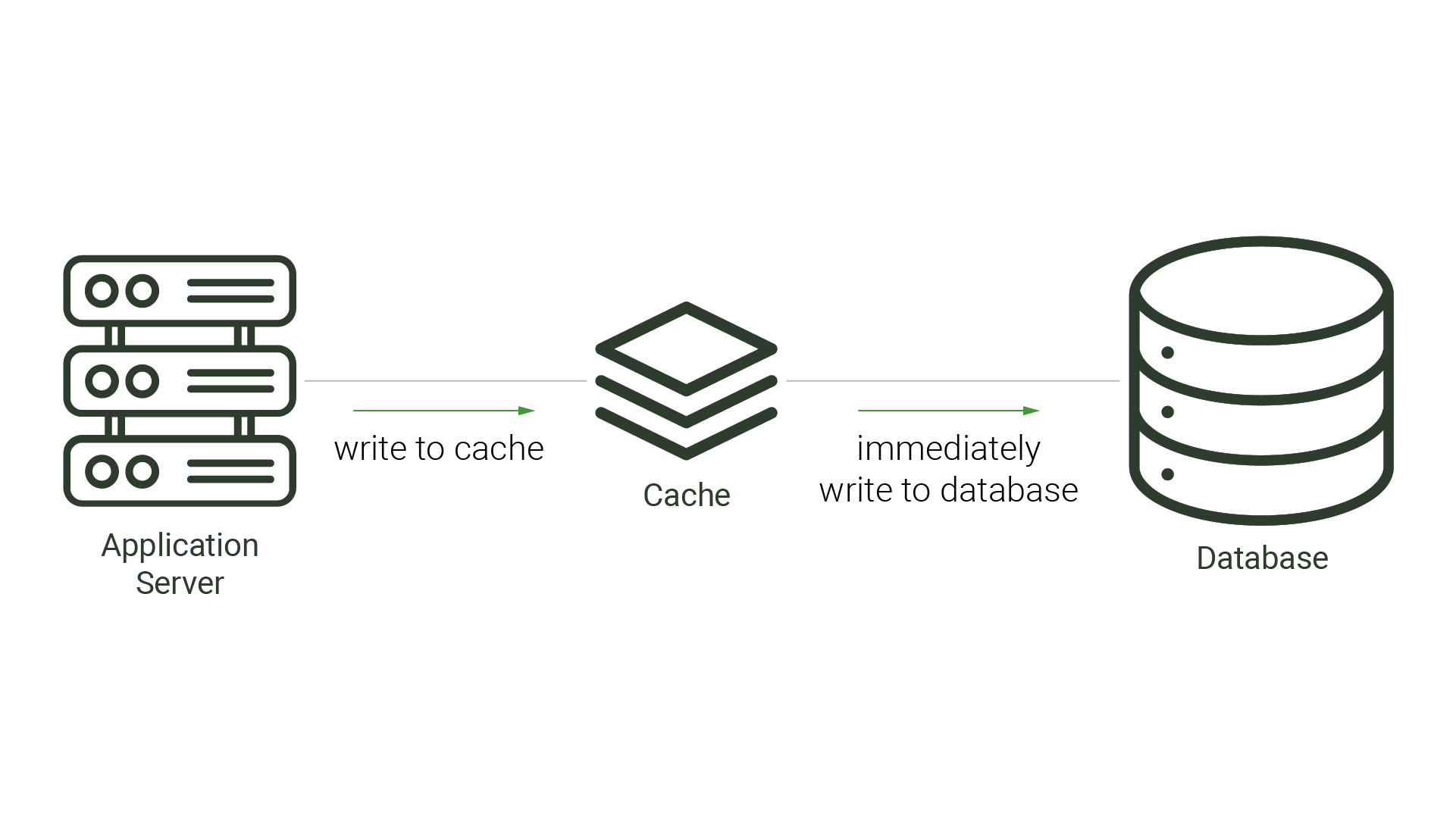

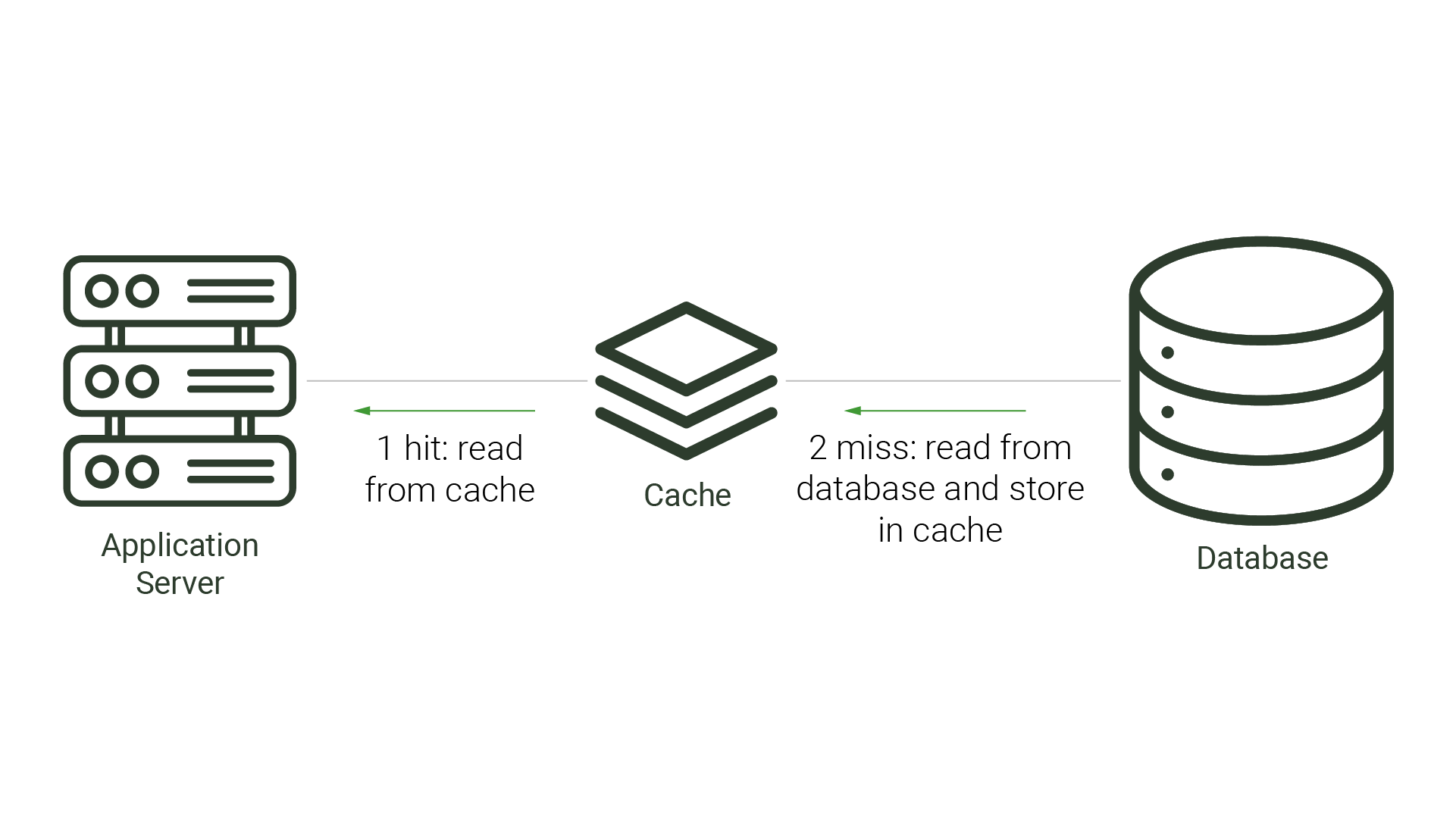

Caching is a viable strategy when there is only one application making changes to the source database. When the architecture is simple, caches can improve performance while avoiding cache inconsistency. This is the case with many types of caching strategies: read-through, write-through, and even cache-aside. Each of these strategies positions the cache either beside the application or between the application and the database. With read-through and cache-aside approaches, the cache is checked for the requested data before the application checks the database. If the data is not found in the cache, this is called a cache miss, and requires the application or cache to check the database for the missing data. Once the queried data is retrieved, it is then stored in the cache for future requests. A write-through cache mirrors what’s in the database, as any writes to the database are first sent to the cache, written there, and then forwarded to the database.

Cache inconsistency becomes a problem when another application or component makes updates to the source database. Because the cache is unaware of these changes, it is possible for the cache to become inconsistent with the source and serve data that is no longer in sync with the source database. This out-of-sync data is referred to as stale data.

There are cache invalidation strategies, such as Time-To-Live (TTL) and polling, that attempt to mitigate this problem.

TTL is a period of time that a value should exist in a cache before being discarded. This approach aims to minimize the presence of stale data. After the data expires and the application’s query to the cache results in a cache miss, the application queries the source database and repopulates the cache. This process incurs additional resource costs and increases demand on the source, especially for expired data that is not stale. This demand is exacerbated when the expiration time is made shorter, and checks on the database for updated data increase. Likewise, longer TTL periods increase the likelihood of stale data, which can be unacceptable for applications requiring timely data accuracy. While TTL can be fairly straightforward to implement, choosing the TTL value that reduces stale data and minimizes database queries is difficult.

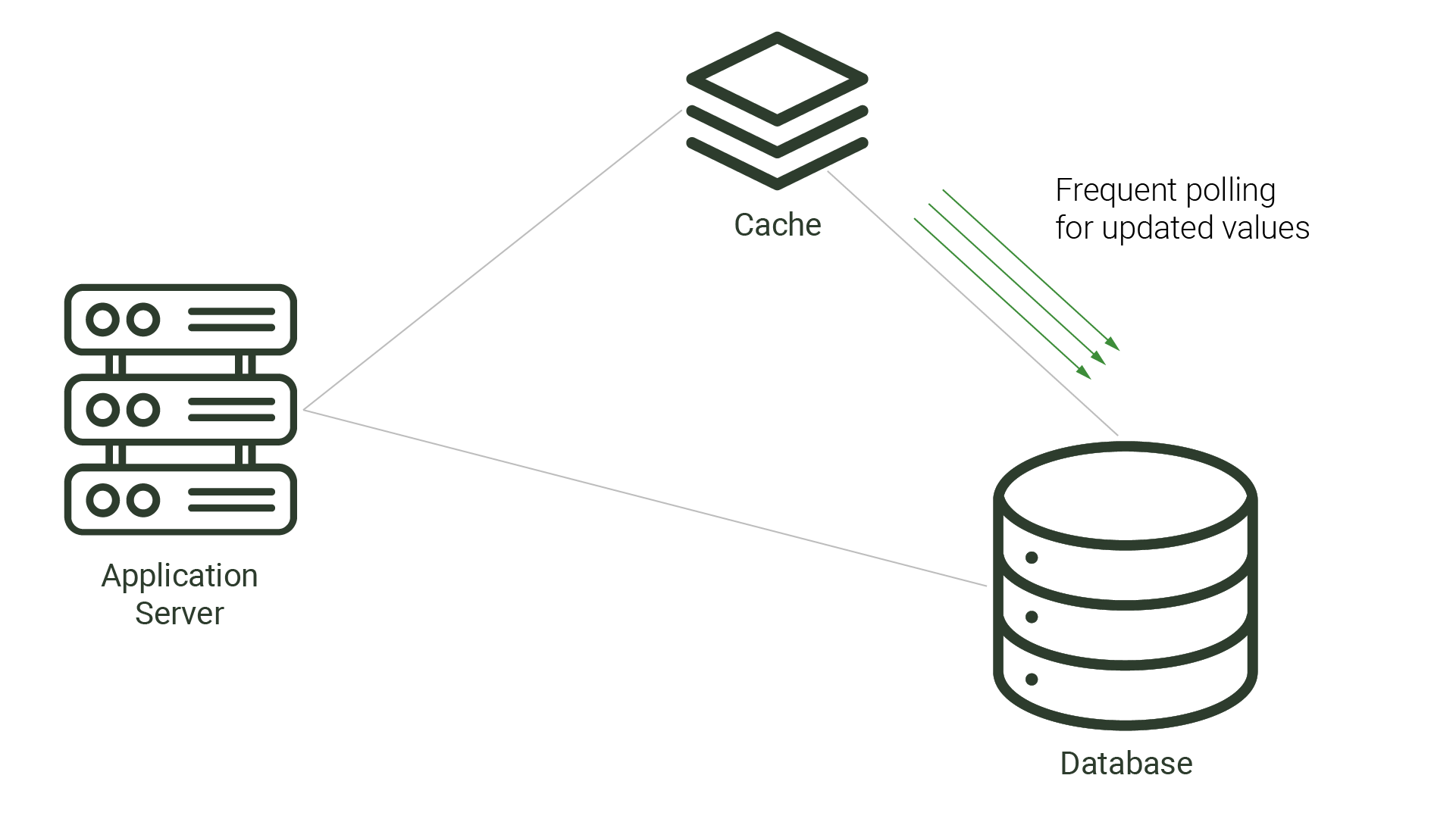

An alternative cache invalidation strategy, polling is when the cache or application periodically checks if the cache’s data is inconsistent with the source database, updating any inconsistent data. Polling typically happens on fixed intervals, such as every 10 seconds, to ensure data consistency. While polling can decrease the time that data remains stale, it also puts extra demand on the source database by running frequent queries.

These cache invalidation strategies - TTL and polling - consist of seeking out and pulling changes from the database. For systems that don’t require constant data consistency and can endure brief moments of stale data, these strategies may be appropriate. However, TTL and polling are not appropriate for systems that require fresh data in near real-time. In the next section, we examine change data capture, a strategy that is not only more appropriate for these types of systems, but can put less demand on the source database.

Change Data Capture

Change data capture has many use cases, including keeping caches in sync with databases.

Change data capture (CDC) refers to the process of identifying and capturing changes in a source - a system that provides data - and then delivering those changes in near real-time to a sink - a system that receives data. Near real-time (or “soft real-time”) refers to the processing of data where systems can tolerate slight delays from a few seconds to a few minutes. This is where most networked communication lies and is opposed to “hard real-time” systems, where data processing is benchmarked against 250 milliseconds (the average human response time) of delay.

CDC can be implemented through a series of different methods, each having their own benefits and tradeoffs.

Timestamp

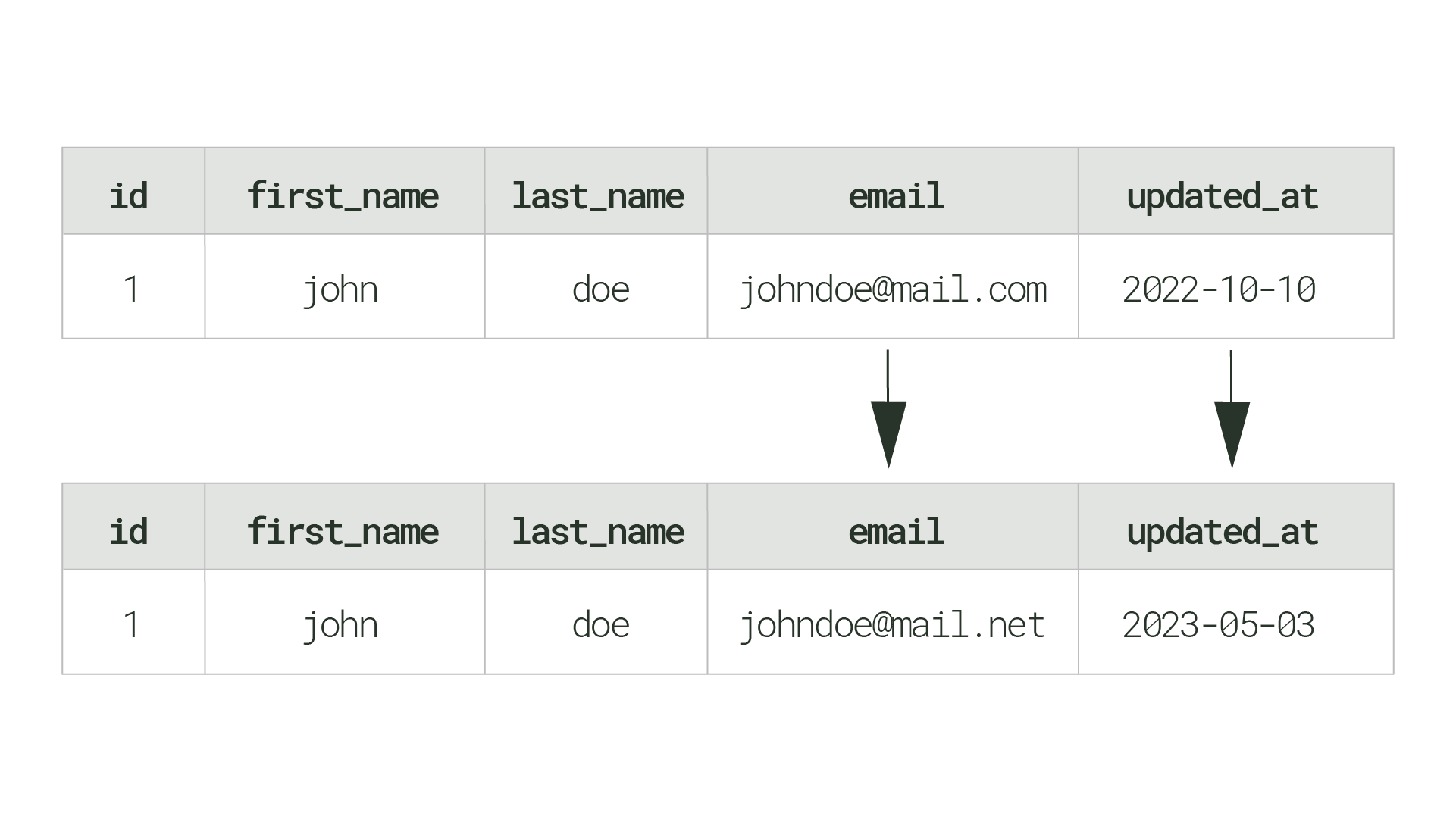

Timestamp-based CDC involves adding metadata columns (e.g., created_at, updated_at) to each database table. One limitation is the inability to perform permanent, hard deletes of rows. Metadata of all changes, including deletes, must persist in order to detect changes. Additionally, to keep the target system in sync, the database needs to be regularly queried for changes, putting additional overhead on the source system.

updated_at column is used to remember when a row was last updatedTrigger

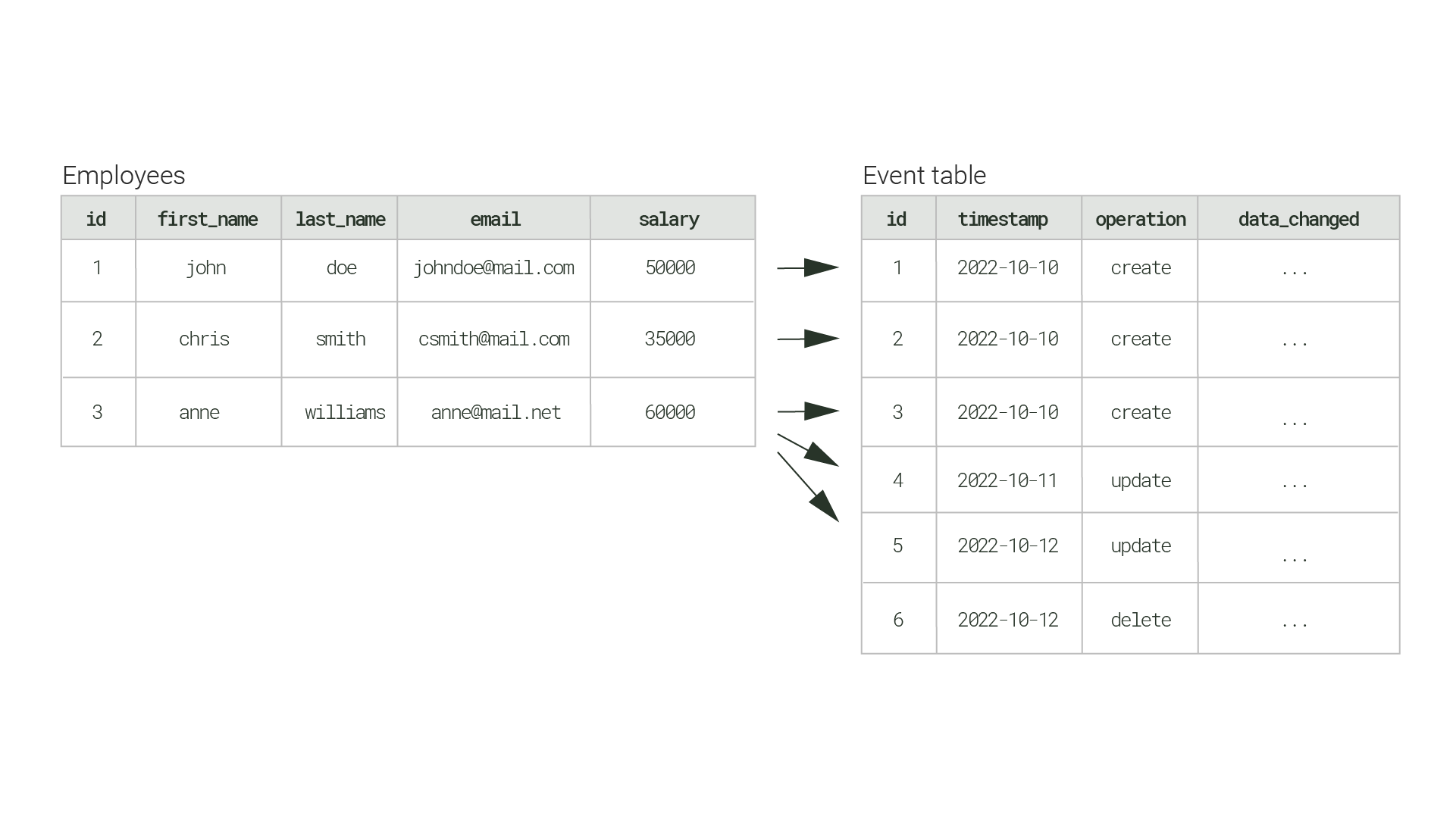

Trigger-based CDC relies on the database’s built-in functionality to invoke a custom function, or trigger, whenever a change is made to a table. Changes are usually stored in a different table within the same database called a shadow table or event table. A shadow table is essentially a time ordered changelog of all operations performed in the database, providing visibility for INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE changes.

While most database systems support triggers, this method has drawbacks. One drawback of trigger based CDC is every trigger requires an additional write operation to an event table. These additional writes impact database performance, especially at scale for write-heavy applications. Another limitation is the event table must be queried to propagate changes to any downstream processes.

Employees table are recorded in the Event tableLog-based

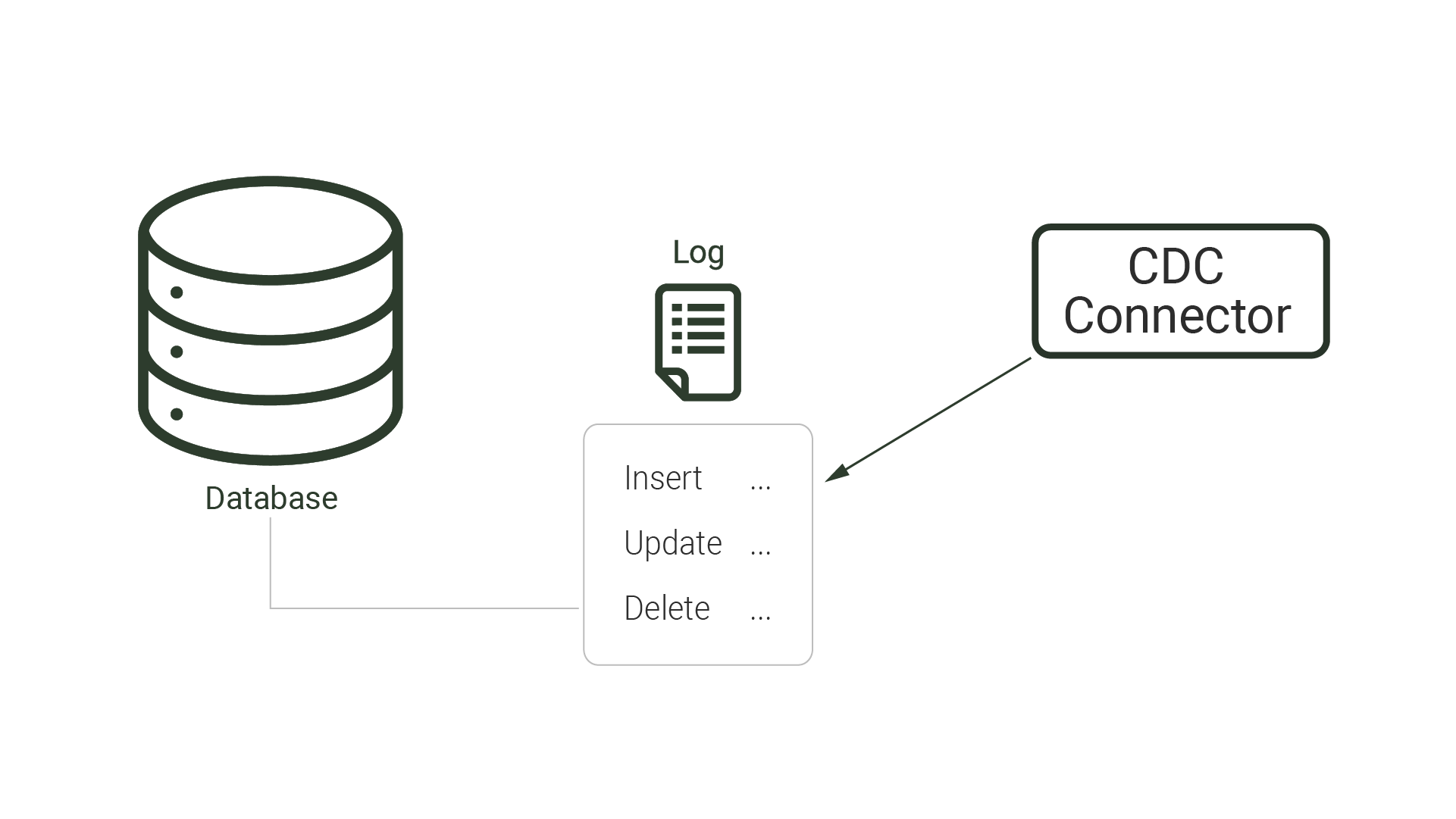

Log-based CDC involves leveraging the database transaction log — a file that keeps a record of all changes made to the database — for capturing change events and delivering those to downstream processes. In log-based CDC, the database transaction log is asynchronously parsed to determine changes instead of formally querying the database. Hence, the log-based method is the least invasive out of the three methods, requiring the least additional computational overhead on the source database.

Although it offers superior performance and reduced latency, the log-based method comes with its own set of tradeoffs. Database transaction log formats are not standardized, so logs between database management systems can vary and vendors can change log formats in future releases. Custom code connectors are also needed in order to read from a transaction log. Additionally, these logs usually only store changes for a particular retention period.

As mentioned, CDC can be used to build a low-latency data pipeline that propagates changes from a database to a cache. Out of the three, log-based CDC takes a non-invasive approach. Because it minimizes impact to database performance, we looked at log-based approaches when considering existing solutions.

Existing Solutions

Log-based CDC is popular among applications requiring up-to-date data in near real-time. Developers have several options for building a log-based CDC data pipeline to replicate data from a source database to a sink cache. Multiple enterprise solutions exist, as well as various open-source projects that can be combined for a custom DIY solution. When deciding which solution to pursue, developers should consider scalability, ease of use and connector types available.

Enterprise Solutions

Multiple enterprise solutions using CDC to replicate data from a source database to a sink cache are available. Prominent solutions include Redis Data Integration and Confluent. Both take care of managing the CDC pipeline and have a number of available source and sink connectors - applications capable of either extracting changes from a data source or replicating changes to a data destination. Redis Data Integration and Confluent are built on top of open-source tools (Debezium and Apache Kafka) and provide additional benefits, like a wide selection of source and sink connectors, architecture management, and built-in scalability.

Enterprise solutions are a good fit for well-funded development teams that want a third-party to manage their architecture and hosting logistics. However, enterprise solutions come with tradeoffs, including vendor lock-in, recurring costs, and reduced infrastructure control. In particular, developers do not have control over how or when infrastructure is upgraded or maintained, which can result in service downtime.

DIY Solutions

An alternative to enterprise solutions, DIY solutions can be built by leveraging open-source tools, like Debezium and Apache Kafka. These tools are open-source, provide a high level of data customization, and offer a wide number of community-maintained source and sink connectors. Customizations include but aren’t limited to filtering data, transforming data, aggregating data, and horizontally scaling CDC pipelines.

Building a DIY solution using open-source tools is a good fit for development teams that prefer to manage their architecture, have a high level of control and customization in their CDC pipeline, and avoid recurring costs from enterprise providers. However, DIY solutions require significant and complex configuration of open-source tools, and developers must provision and manage appropriate infrastructure for the CDC pipeline. The time to learn, implement, and configure these technologies can slow down teams looking to quickly deploy a CDC pipeline.

Introducing Willow

Given the tradeoffs that accompany enterprise CDC solutions and the complexity of a DIY solution, our team identified a gap in the solution space. Willow was developed as an open source, user-friendly framework designed to maintain cache consistency by creating a near real-time CDC pipeline that monitors changes in a user's PostgreSQL database and reflects row-level changes in a user's Redis cache.

Willow’s user-friendly UI abstracts away configuration complexities we encountered in the DIY solutions by guiding users through a set of forms to set up a pipeline. Once a pipeline is created, users can set up additional pipelines, view a list of existing pipelines and their configuration details, and delete a pipeline.

Willow can be deployed on users’ server of choice, allowing users to retain infrastructure control and avoiding vendor lock-in. While Willow only has a single source connector for PostgreSQL and a single sink connector for Redis, the simplicity of setting up and configuring these connectors into a CDC pipeline reduces overall deployment time and cost.

Willow pipelines connect a PostgreSQL database and a Redis cache, storing database rows in the Redis cache as JSON objects Updates made to the database are passed on to the cache in near real-time.

Demonstration

The best way to understand what Willow does is by seeing it in action. In the video below, a PostgreSQL terminal logged into the willow database is on the left and RedisInsight - a Redis GUI for visualizing a cache's contents - is on the right. A Willow CDC pipeline connects the source PostgreSQL instance on the left to the sink Redis cache on the right.

Initially, the PostgreSQL store table and the Redis cache are empty. Once a row is inserted into store, Willow replicates the row in the cache. After refreshing RedisInsight, we can see that the row inserted into our PostgreSQL table has been replicated in our Redis cache.

Using Willow

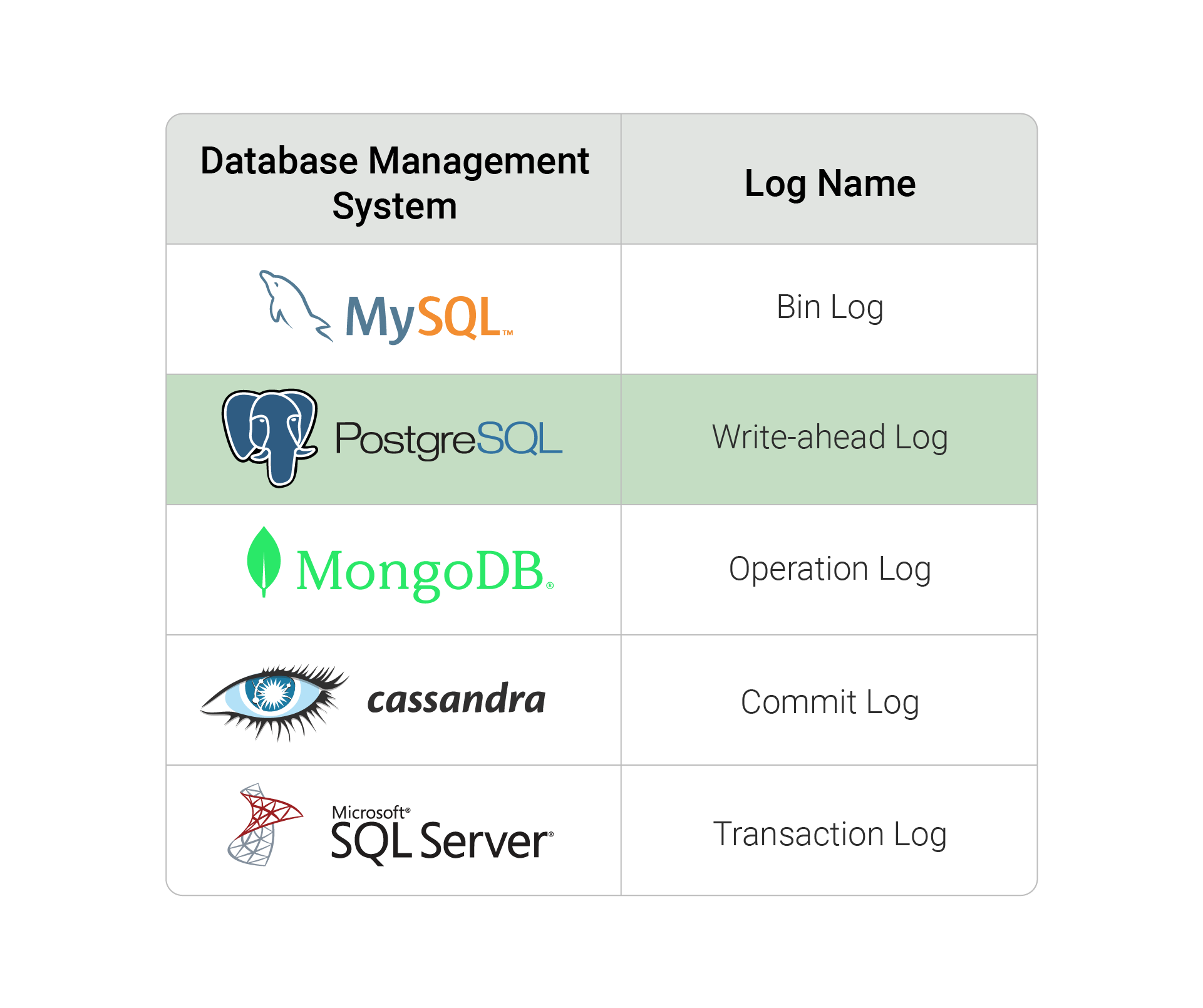

- Initially, users are greeted with a "Welcome to Willow" page, offering an invitation to create a CDC pipeline with a click of a button.

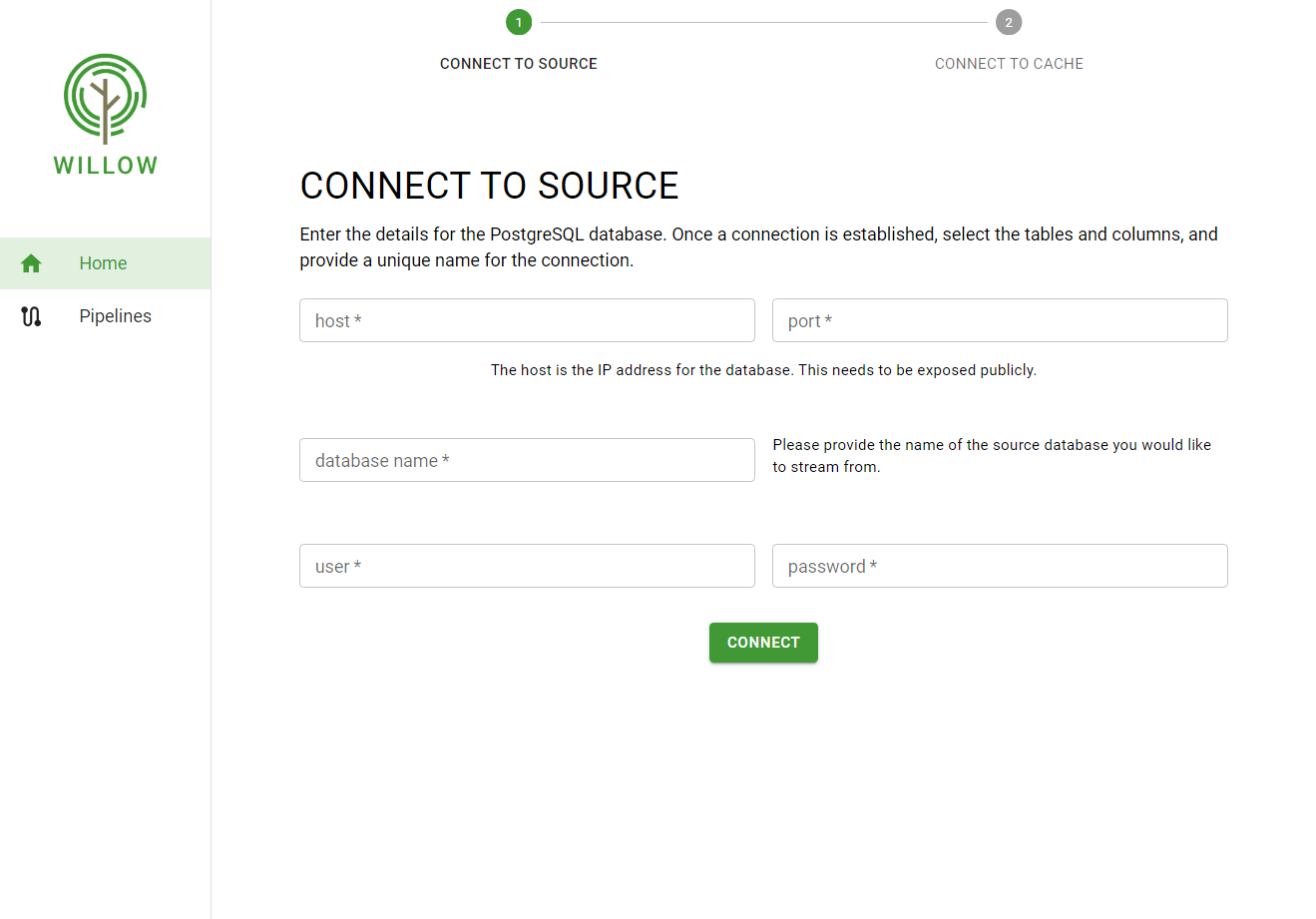

- The user is then asked to enter credentials for a PostgreSQL source.

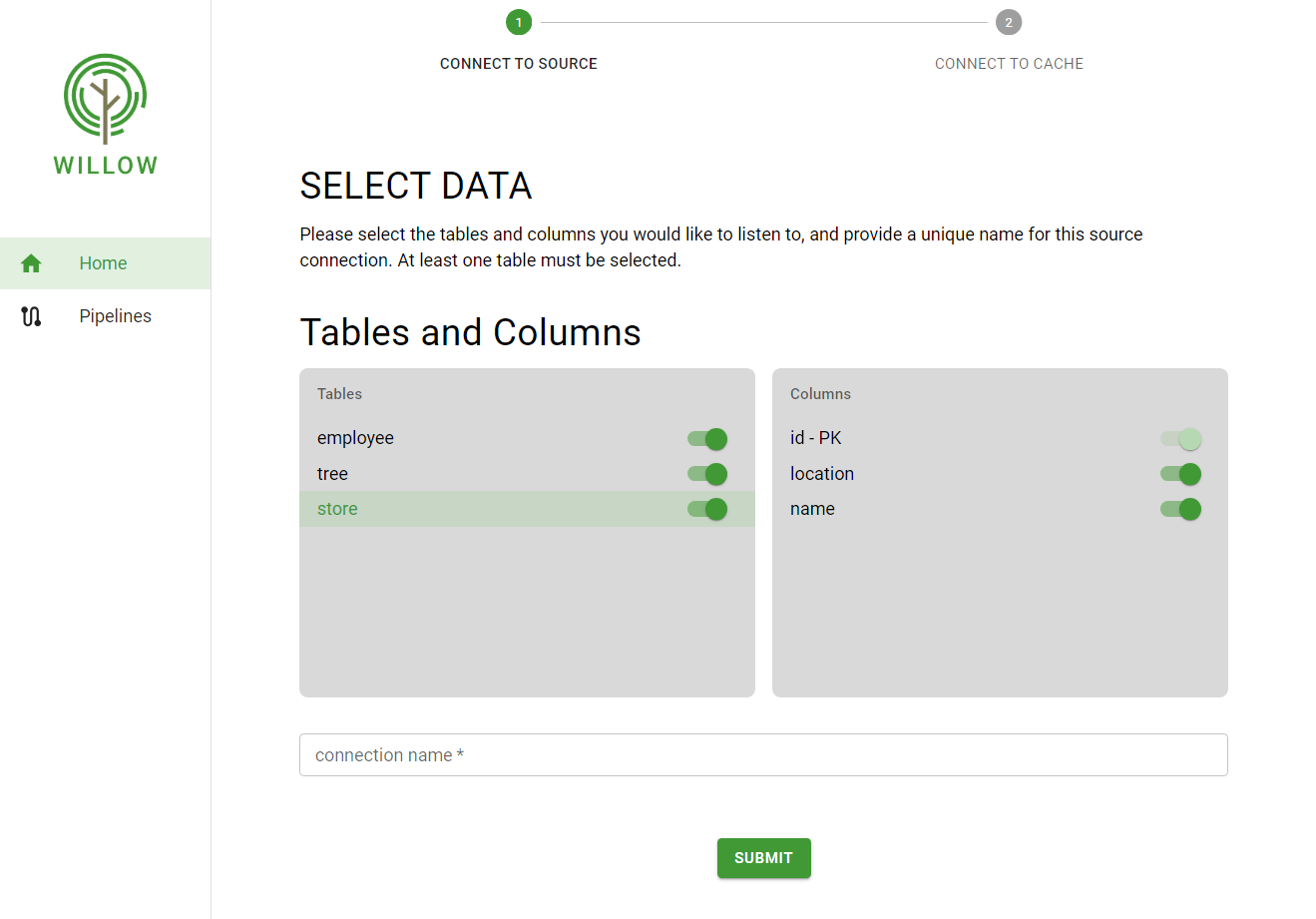

- Once a connection to the source database is established, the user can view and select the tables and columns to be captured. The user must also provide a name for the source connector.

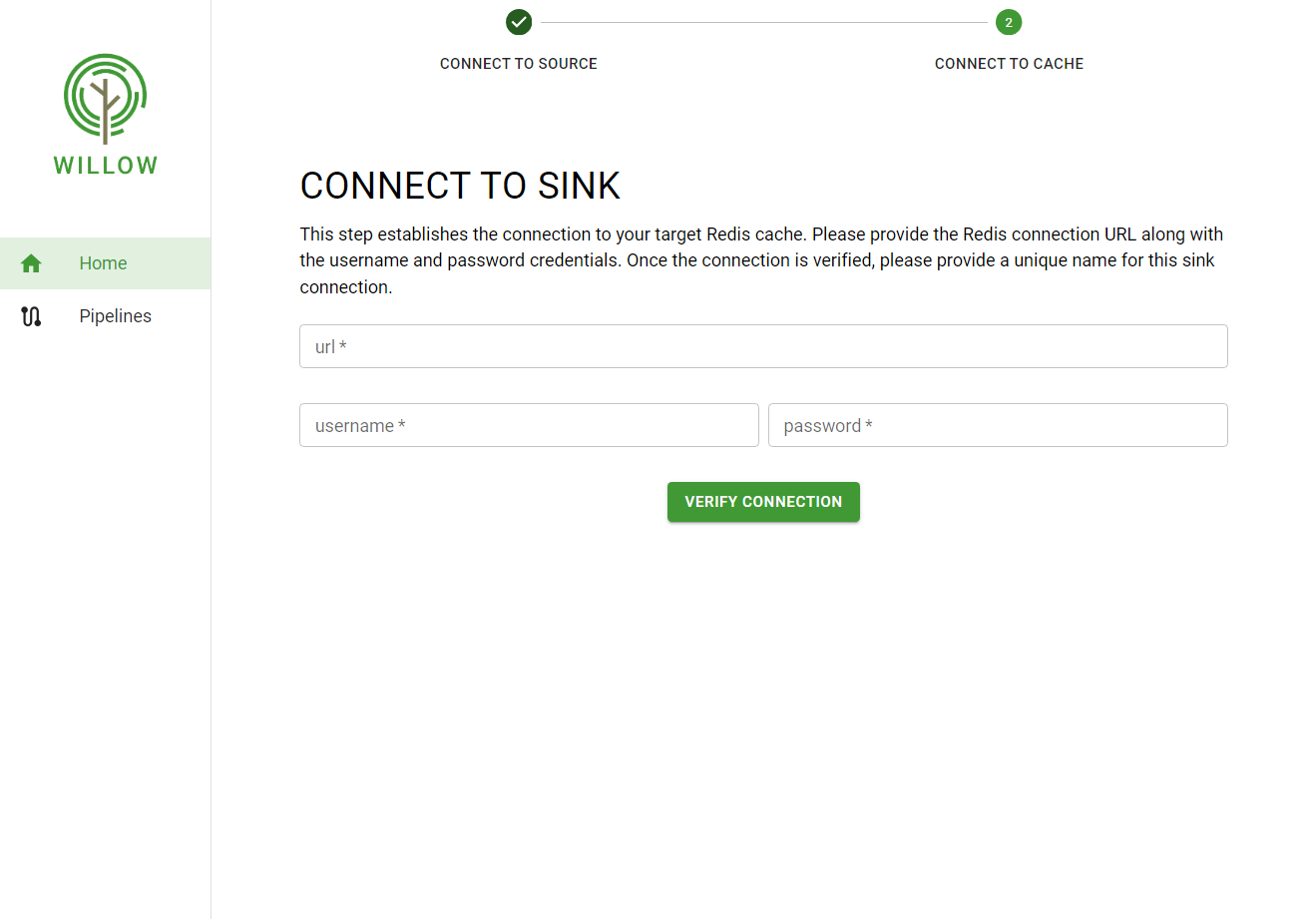

- After data selection, users must enter the Redis credentials and verify the connection to the cache.

- Once the sink connection is verified, users must provide a name for the sink connection. This completes the pipeline setup.

Implementation

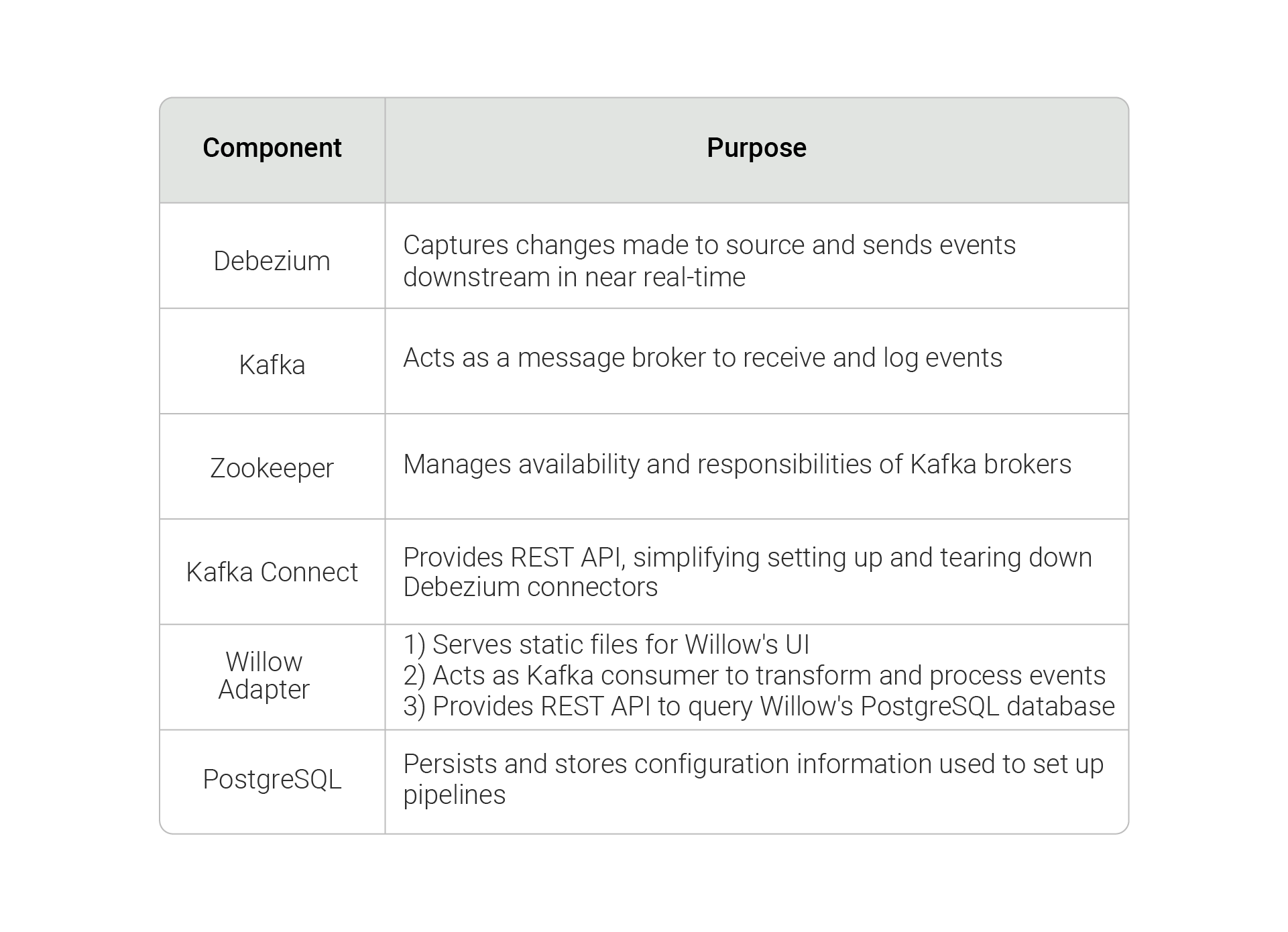

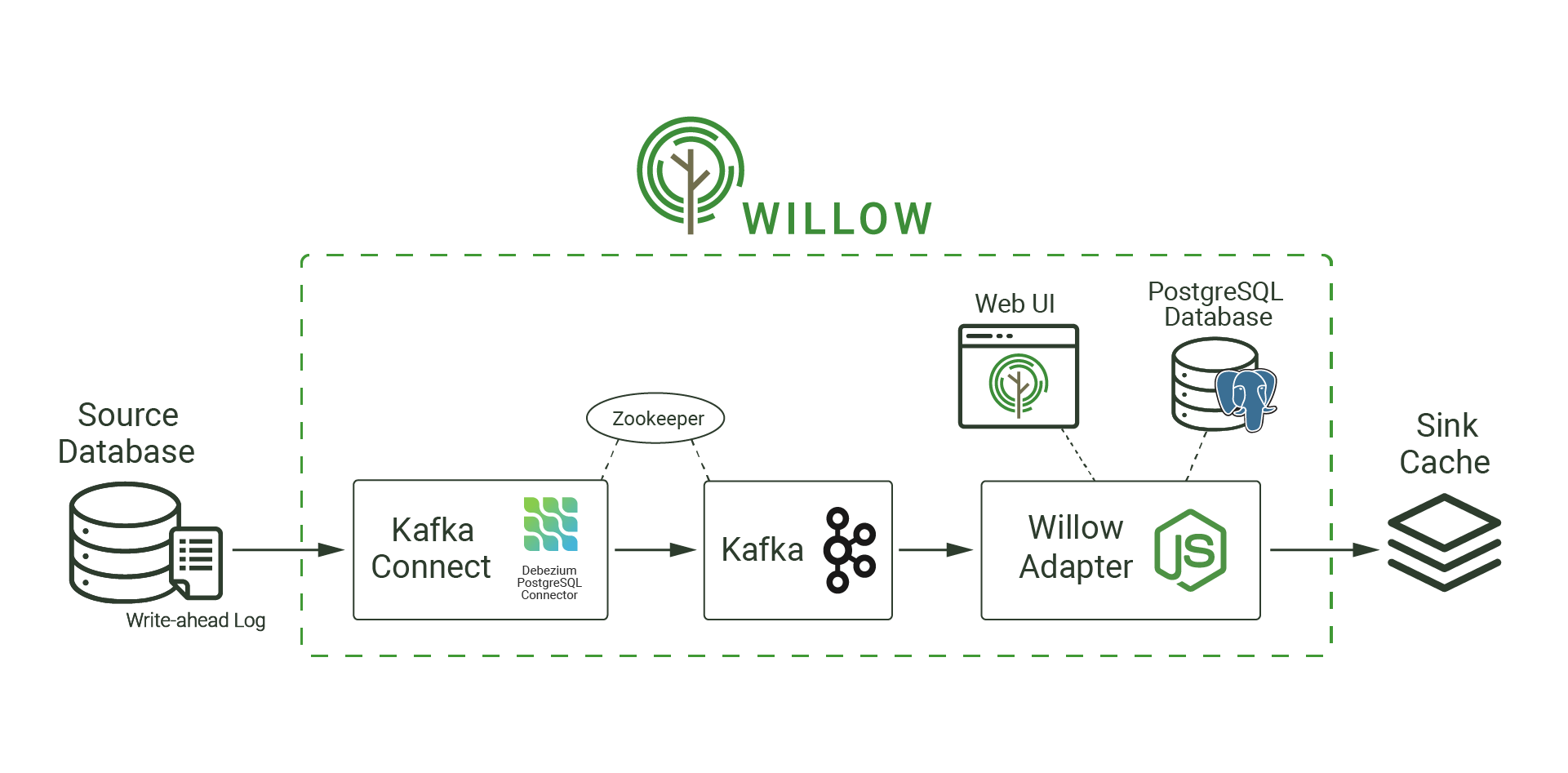

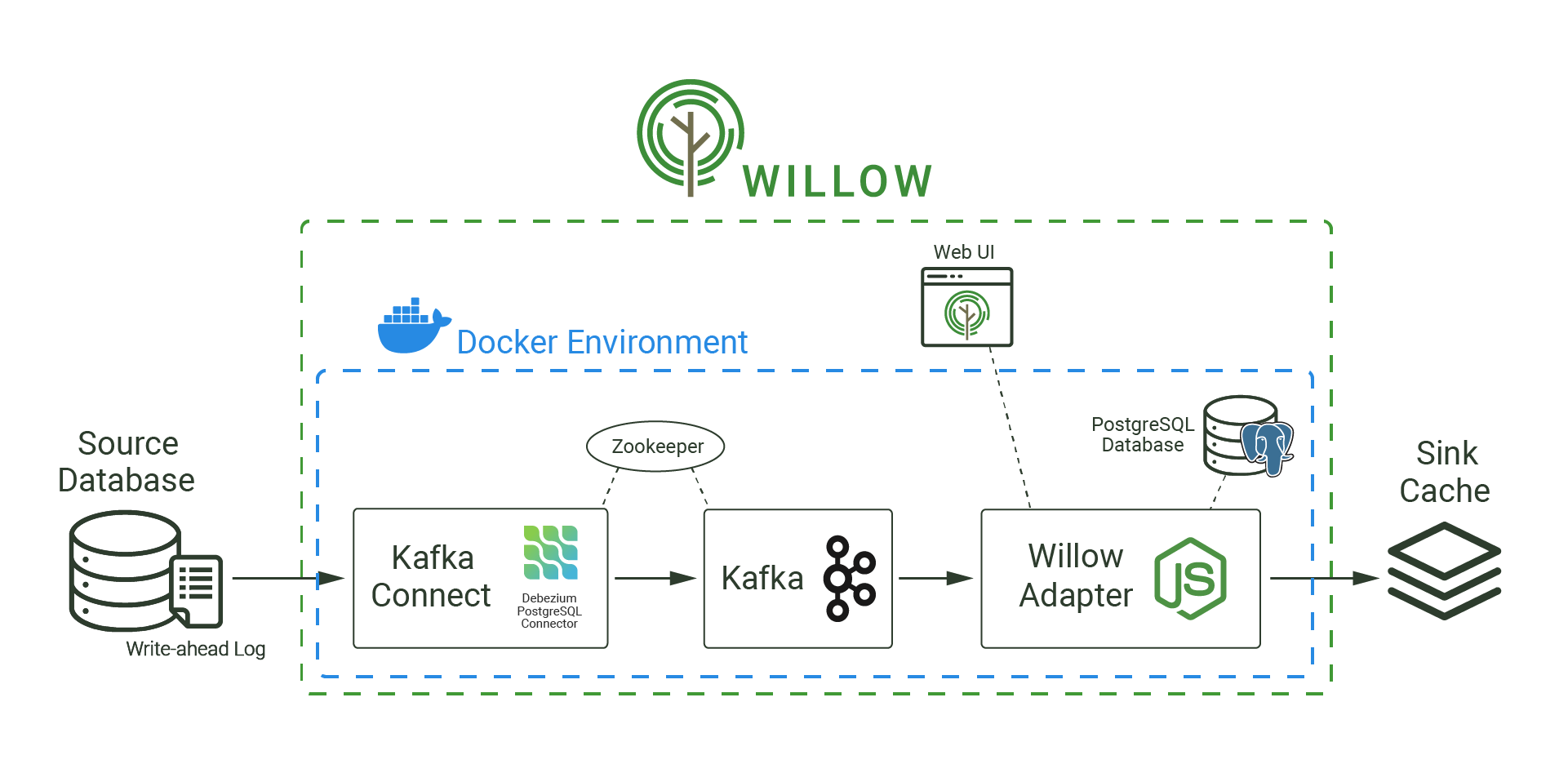

Willow leverages open-source technologies - Debezium, Apache Kafka, Apache Zookeeper, Kafka Connect, PostgreSQL - to create CDC pipelines and ensure that changes in source databases are updated in sink caches in near real-time. This section introduces Willow's components and explains their roles within Willow’s architecture.

Debezium

When we first sought to address the cache consistency problem, we prioritized open-source CDC tools that are widely used, are well documented, and implement log-based CDC. This criteria is how we landed upon Debezium.

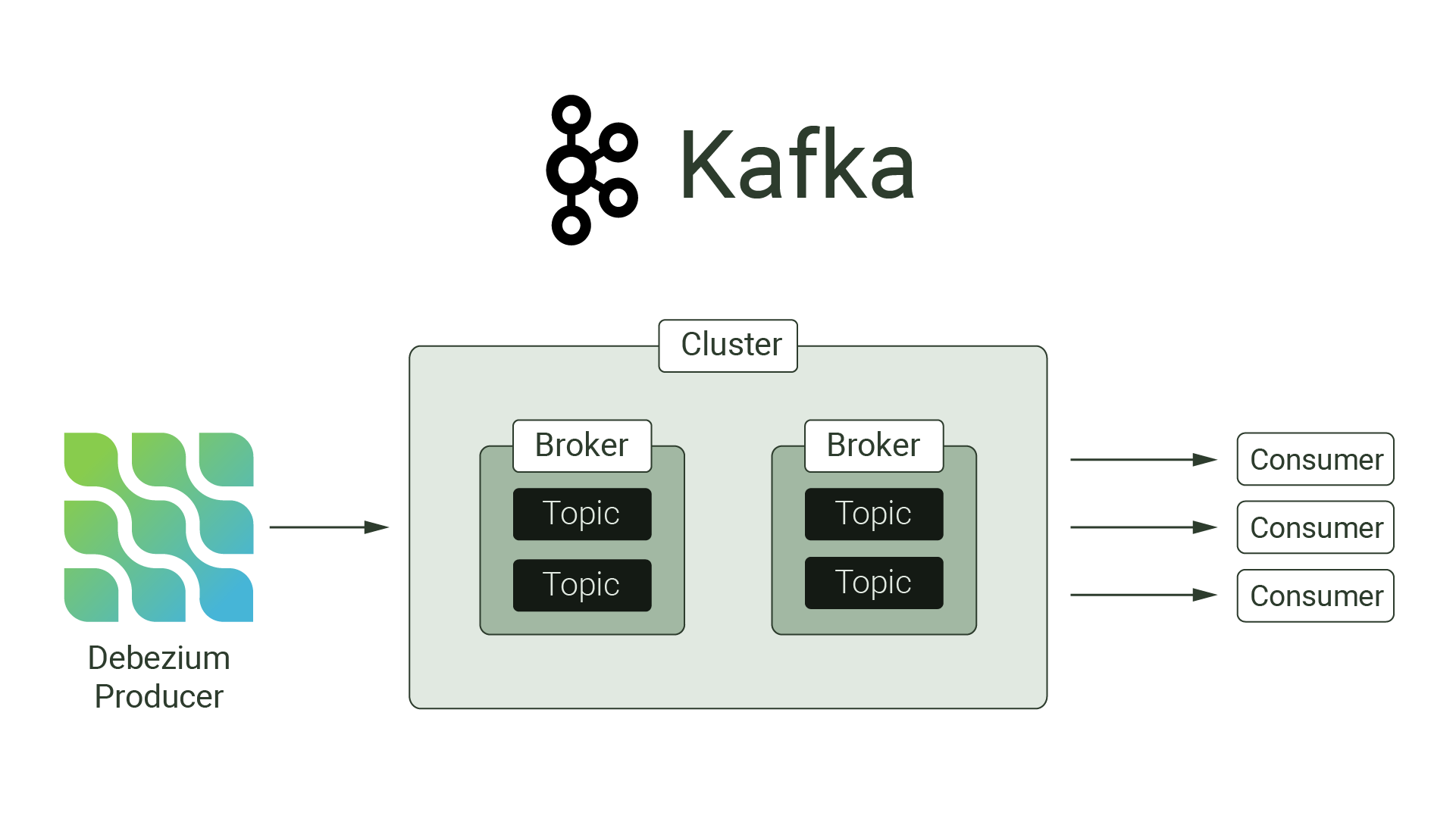

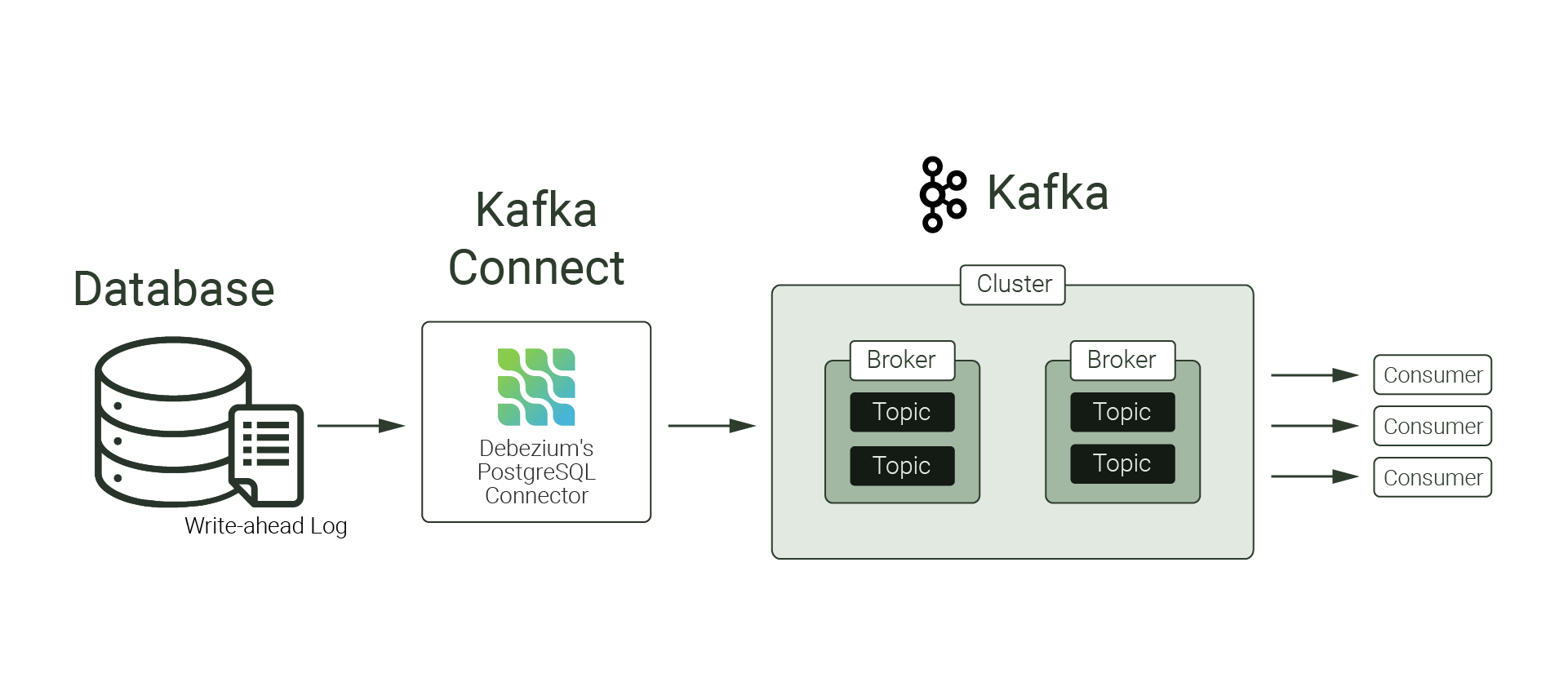

At the heart of Willow lies Debezium, an open-source distributed platform for change data capture. Debezium monitors databases’ transaction logs and captures row-level changes for operations such as INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE. It produces events for such changes, and pushes those events downstream to an event-consuming process.

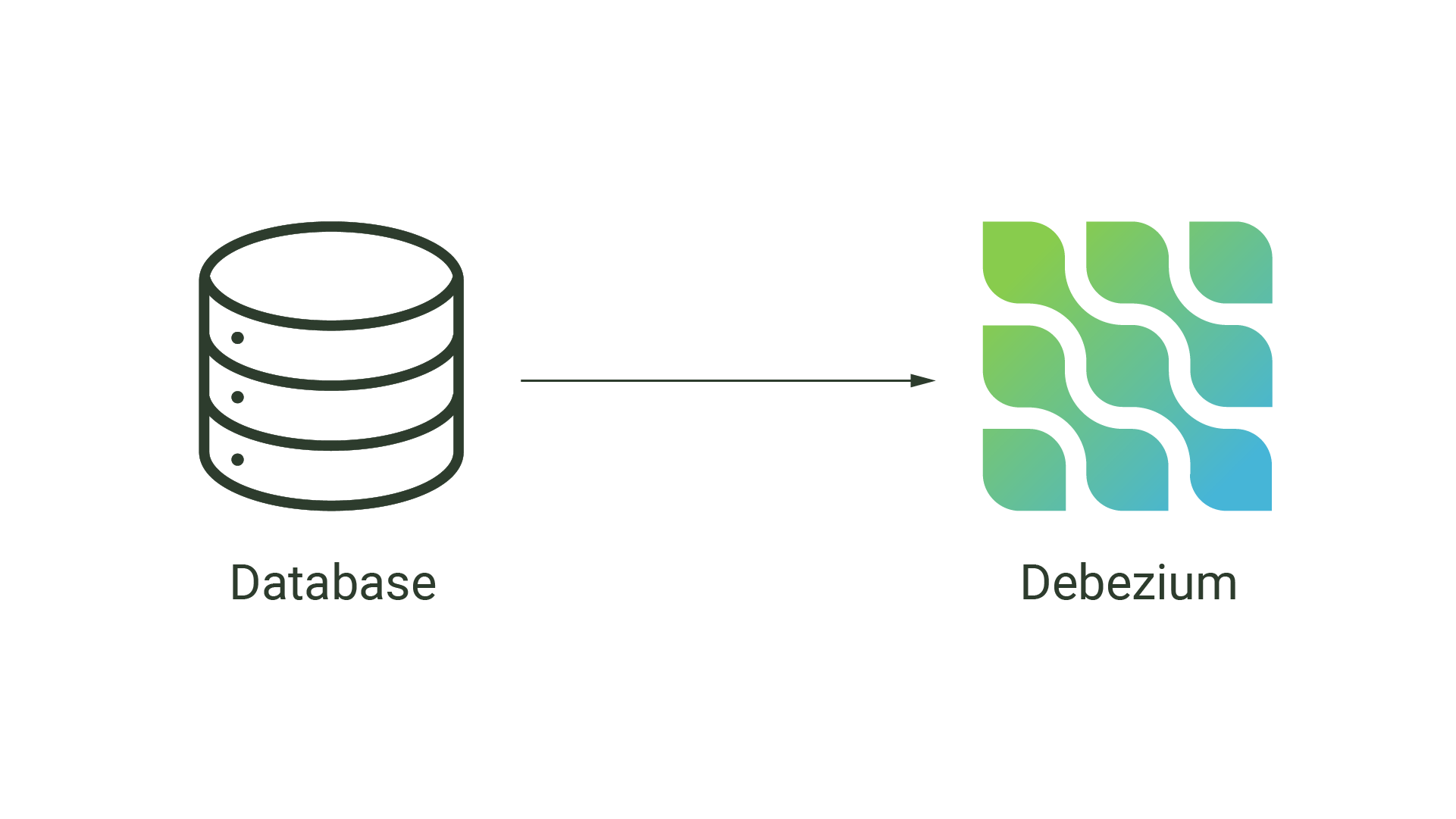

Previously, when we defined change data capture, we outlined three methods for implementing CDC. We highlighted that log-based CDC is arguably superior to the other two approaches, but a downside is that transaction logs varied in format across database management systems. For example, MySQL’s binlog is different from PostgreSQL’s write-ahead log, despite their similar purposes.

Debezium addresses this lack of standardization by providing connectors. These connectors read from the database and produce events that have similar structure, regardless of the type of source database. Supported databases include PostgreSQL, MongoDB, and MySQL, among others. In other words, Debezium abstracts away the complexity of dealing with unstandardized transaction logs, and provides standardization for changes to be captured and handled downstream.

Debezium, to the best of our knowledge, is the only open-source CDC tool that can capture from a variety of databases. Debezium's in-depth documentation and wide usage make it a reasonable tool for Willow to use.

Apache Kafka

Apache Kafka is an open-source, distributed event streaming platform.

While Kafka is a broad topic and has many moving parts, the core workflow is simple: producers send messages to Kafka brokers, which can then be processed by consumers. Within Willow, Kafka is a message broker that stores streams of Debezium events.

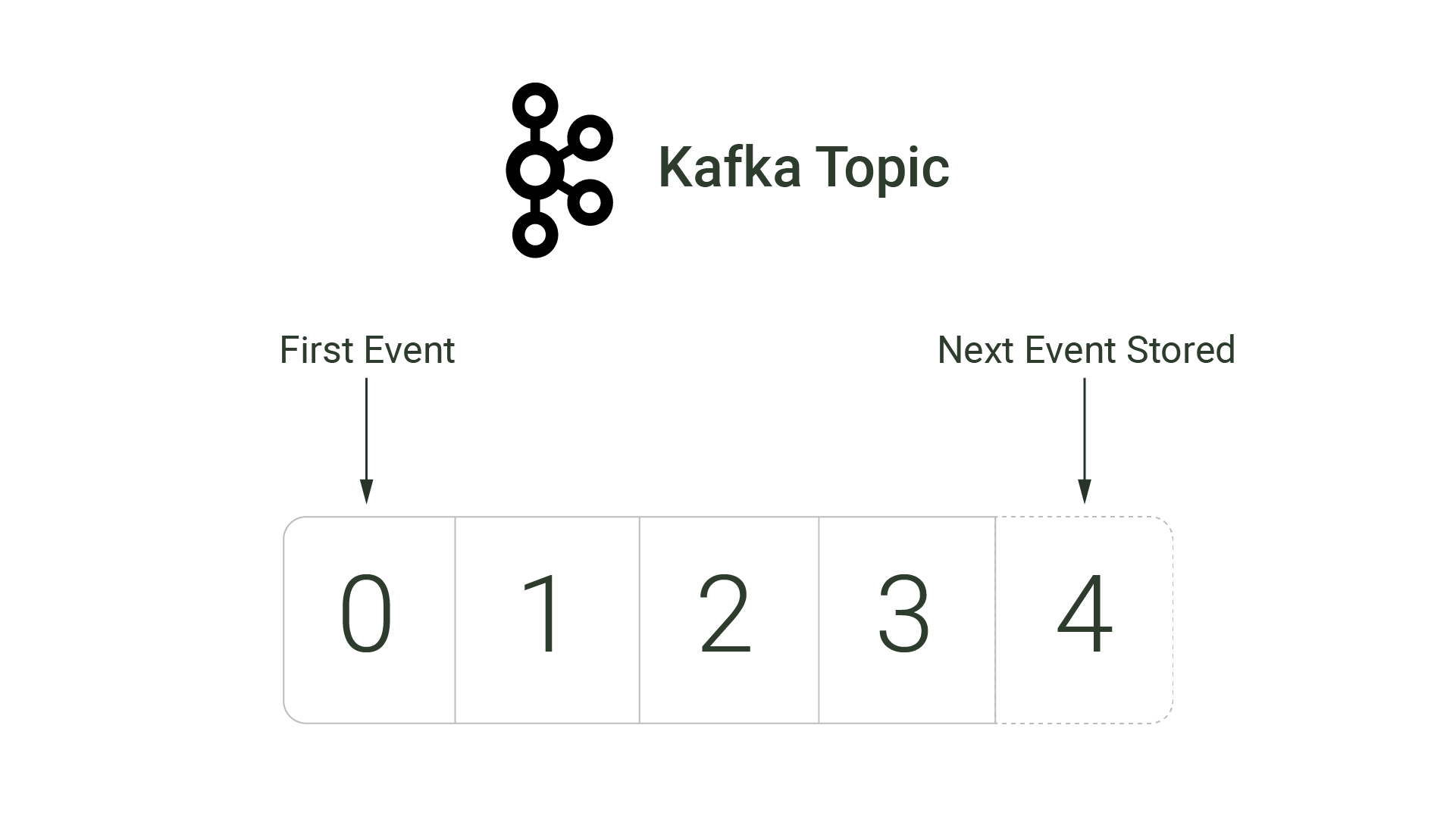

At its core, Apache Kafka consists of append-only logs, where messages are stored in sequential order. Kafka calls these logs topics. Topics are where events - records of a state change - are stored.

A single broker, or individual Kafka server, is responsible for storing and managing one or more topics. A group of brokers, called a cluster, work together to handle incoming events. Brokers within a cluster can be distributed across a network, and clustered brokers can replicate each others’ topics to provide data backups.

Because Kafka can be distributed across different servers and enable data replication, it is highly scalable and fault tolerant. Furthermore, its core data structure, an append-only log, enables fast reads and writes.

Apache Kafka clusters can be handled by Apache Zookeeper, which manages metadata on Kafka’s components. Zookeeper functions as a centralized controller.

We chose Apache Kafka for a few reasons. The first is that Debezium is natively built on top of it; there is wide support and documentation for streaming Debezium events to Kafka, and how such events can be processed by downstream consumers. The second, related reason is a tool called Kafka Connect. Kafka Connect is a framework that allows one to set up, update, and tear down source and sink connectors that use Kafka as a message broker.

Debezium has three deployment methods: Debezium Engine, Debezium Server, and deployment through Kafka Connect. Debezium Server and Debezium Engine largely lack the ease of use provided by Kafka Connect’s REST API, and would require specifying a message broker. The third deployment method - deployment via Kafka Connect - streams changes directly to Apache Kafka. It provides an easy to use REST API for configuring and setting up connectors to Apache Kafka. Using Kafka Connect allows us to leverage Apache Kafka’s advantages, which includes persistence of records to disk in a way that is optimized for speed and efficiency.

Apache Kafka’s robust features, along with the tools that surround it - most notably, Kafka Connect - make it a logical message broker to be used with Debezium.

Willow Adapter

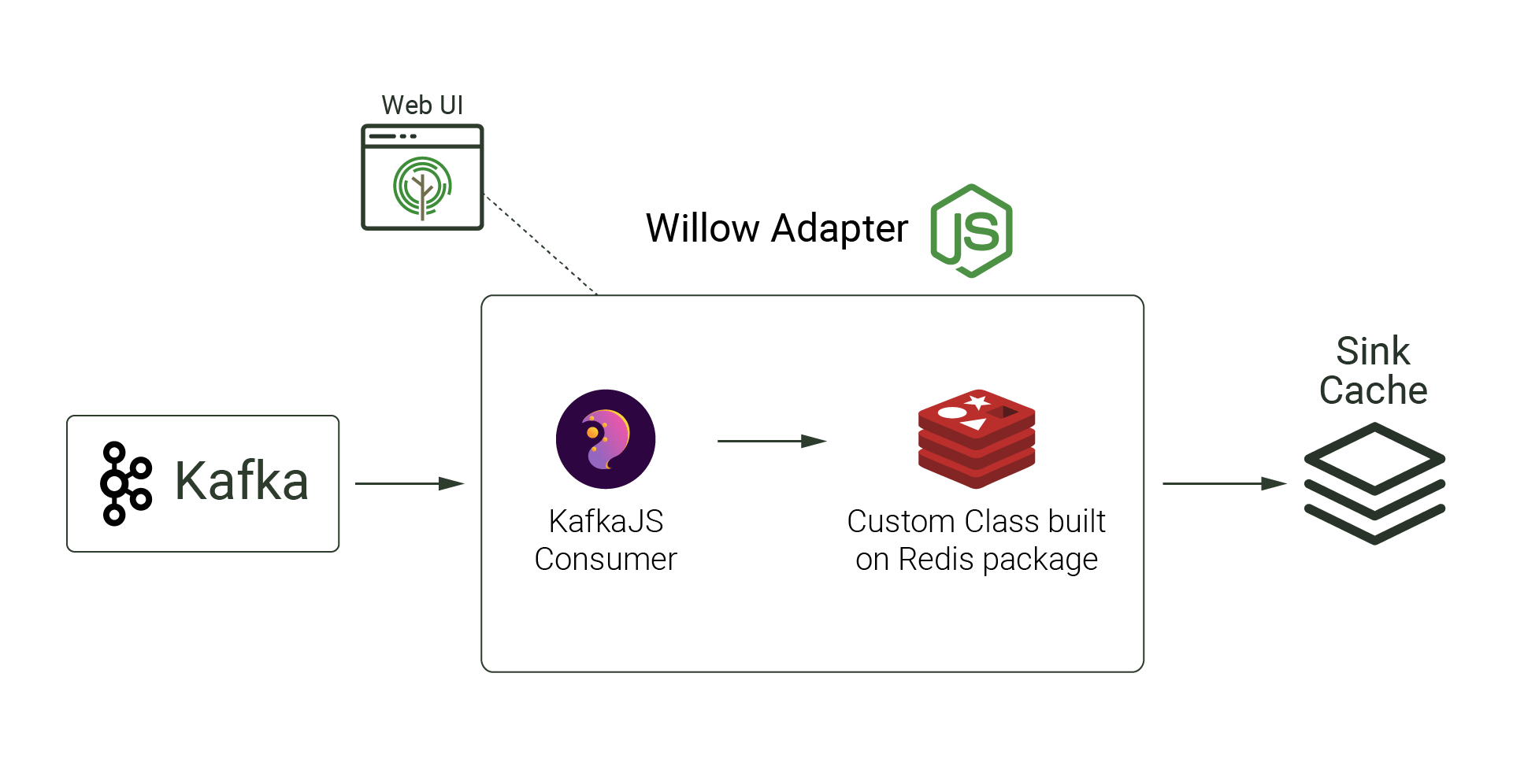

While Kafka enabled us to have a reliable streaming platform to publish database change events captured by Debezium, we still needed a way to consume those events and transform them into a suitable format for a cache. Initially, we researched a Redis Kafka Connect connector that consumes events from a Kafka topic and writes to a Redis cache. This connector converts events into Redis data types and generates a unique Redis key for each row. When assessing this connector, we were able to reflect CREATE and UPDATE changes to the cache, but DELETE changes were not reflected in the cache. Also, additional Kafka Connect metadata was inserted into the cache, which was undesirable since we only want database rows to be reflected in the cache.

The Redis Kafka Connector connector was not optimal for Willow's needs, so we chose to implement our own custom Redis connector - a Willow Adapter for Kafka built with NodeJS. The Willow Adapter provides similar functionality to the Redis Kafka Connect connector, but it handles database level deletes appropriately by removing the associated data from the cache. The Willow Adapter also only inserts database row information - no Kafka Connect metadata is inserted. To consume messages from a Kafka topic, the KafkaJS npm package was used. To process those messages and update the cache, a custom class was created that leverages the Redis npm package.

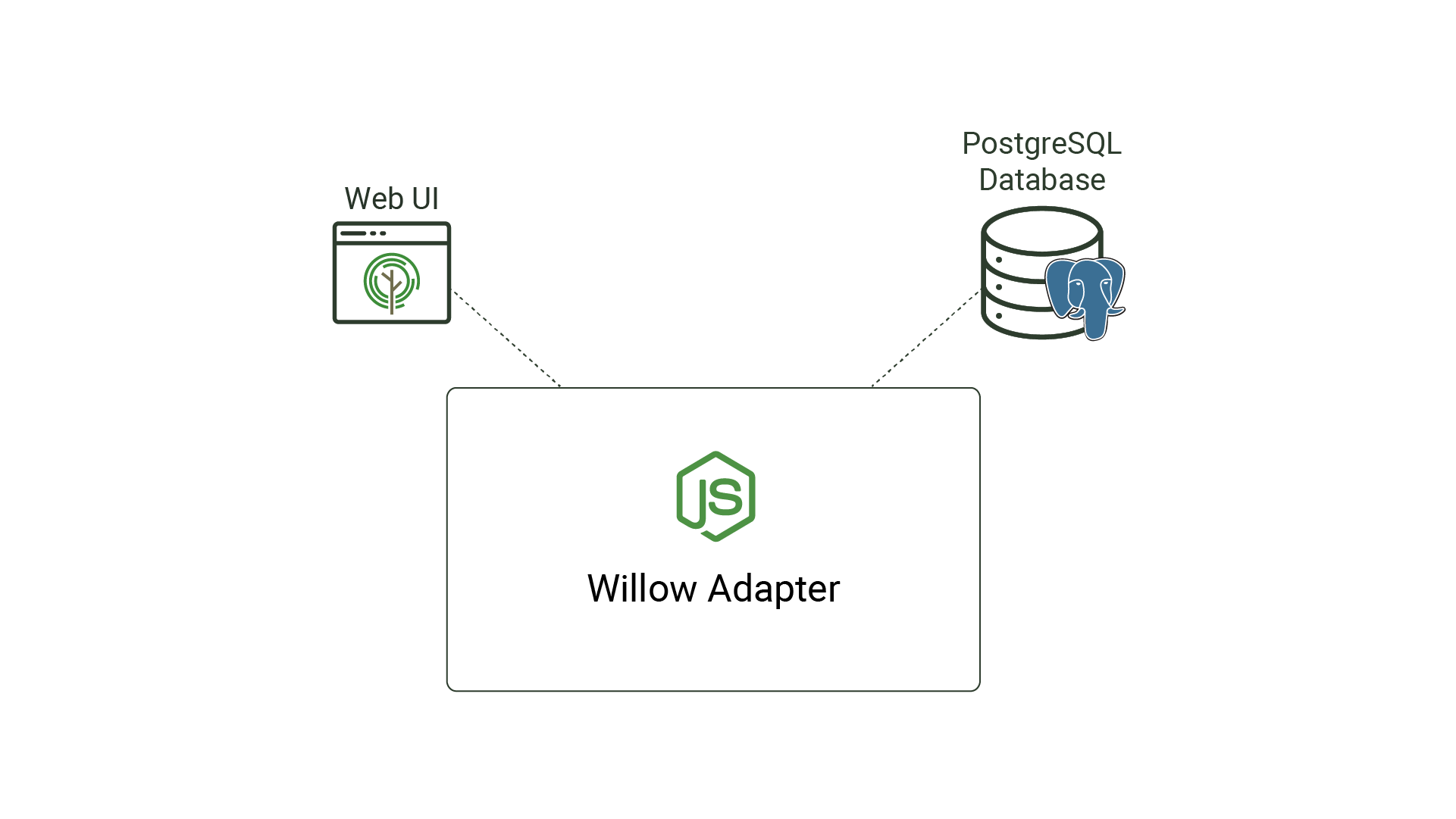

In order to provide a user-friendly UI for building a CDC pipeline, the Willow Adapter both provides a React application and acts as the REST API for Willow’s UI, simplifying setup and teardown of each pipeline.

PostgreSQL

The final component of Willow's architecture is a PostgreSQL database. PostgreSQL is an open-source, relational database management system (RDBMS) that stores structured data in tables. Data within PostgreSQL can be retrieved by using Structured Query Language (SQL) queries.

An RDBMS works well when data follows a well-defined format and associations exist between different data entities. Willow uses PostgreSQL for its RDBMS, which is appropriate since associations exist among Willow's various entities; notably, each pipeline is associated with a source and sink. Configuration details for sources and sinks also follow a well-defined format, aligning with the type of structured data PostgreSQL excels at persisting. By storing pipeline information within a PostgreSQL database, Willow can redisplay existing pipeline information in its UI.

Architecture

As shown, Willow’s pipeline is built upon various open-source tools. The components can be summarized as follows:

To minimize potential configuration issues with installing Willow, we use Docker. Containerizing Willow also makes sense from a long-term perspective; Docker supports various orchestration tools like Kubernetes or Docker Swarm that allows users to manage and scale containers. In other words, Docker is not only portable and consistent across various environments, but it is also horizontally scalable. Its ease of use and portability make it an important piece of Willow.

The final architecture is as follows:

Challenges

Willow's development encountered two main technical challenges: Debezium configuration and event transformation.

Debezium Configuration

Multiple Pipelines Sharing a Replication Slot

One of the challenges was centered around multiple pipelines sharing a replication slot. A replication slot is a PostgreSQL feature that keeps track of the last-read entry in the write-ahead log - PostgreSQL’s transaction log - for a specific consumer. For Willow, a consumer is equivalent to a pipeline.

In an early version, Willow reused a single replication slot for every pipeline connected to a PostgreSQL server, but only a single pipeline received changes and the remaining pipelines received none. This occurred since all pipelines for a single PostgreSQL server shared a replication slot and only one pipeline can consume from a replication slot at a time. However, pipelines connected to the same PostgreSQL server should be considered independent entities that consume all relevant changes.

In order to ensure multiple pipelines using the same PostgreSQL server receive every change, Willow creates a unique replication slot for each pipeline. By doing so, Willow enables each pipeline to concurrently and separately read from the write-ahead log.

A tradeoff to this approach is that a new replication slot is created in the PostgreSQL server each time a pipeline is generated. This can result in multiple replication slots, creating opportunities for inactive slots when associated pipelines are torn down. Inactive replication slots force PostgreSQL to indefinitely retain all write-ahead log files unread by the associated pipeline, filling up disk space. Database administrators must carefully monitor and purge any inactive replication slots to avoid unnecessary write-ahead log retention.

Working with Minimum Privileged User

The second challenge was ensuring source connectors are successfully created when Willow is provided a database user that does not have SUPERUSER privileges. A PostgreSQL SUPERUSER bypasses all permission checks and accesses everything in the server. A minimum privileged user, on the other hand, only has sufficient permissions for Willow to create a source connector and replicate specific tables within the PostgreSQL server. These privileges are REPLICATION, LOGIN, database level CREATE, and table level SELECT privileges.

Debezium successfully creates a source connector to a PostgreSQL server when the provided PostgreSQL user either is a SUPERUSER or a minimum privileged user. Willow follows the principle of least privilege - the idea of providing users and programs only the minimum level of access needed to perform their responsibilities - by allowing end users to provide a minimum privileged PostgreSQL user.

Debezium uses the minimum privileged user to create a publication. A publication is a database-scoped sequential list of INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE, and TRUNCATE changes for selected tables and are how pipelines receive data for what changes occur in those tables.

Initially, Willow worked well when provided a SUPERUSER but failed when given a minimum privileged user. The core issue came down to how Debezium creates publications in the source database and how Willow was configuring Debezium with a minimum privileged user.

Initially, Willow used Debezium's table.exclude.list setting to specify which tables should not be replicated. By process of elimination, Debezium would then attempt to replicate all of the non-excluded tables in the database. However, if private tables exist in the database that the minimum privileged user does not have access to, these tables would not be visible when Willow queried the database to determine what tables exist, and those non-visible tables would not be listed in table.exclude.list. As a result, Debezium’s publication creation would fail since the publication contained tables inaccessible to the minimum privileged user.

table.exclude.listThis issue was resolved by using Debezium's table.include.list instead of its exclude counterpart. This strategy of white-listing instead of black-listing tells Debezium exactly which tables to include in the publication, preventing Debezium from including tables inaccessible to the minimum privileged user.

table.include.listEvent Transformation

Events generated by Debezium take the shape of a key-value pair, representing an individual table’s row change. The key contains information about the row's primary key value, and the value contains information about the type of change and the row's updated values.

Willow uses a combination of the event’s key and value to determine the Redis key, which follows the format database.table.primarykey.

When transforming events into Redis key-value pairs, Willow handles a few edge cases: tombstone events, tables without primary keys, and tables with composite primary keys.

Tombstone Events

When a row is deleted, Debezium generates two events. The first is a DELETE event containing information about the deleted row. The second, called a tombstone event, has a key property containing the deleted row’s primary key and a value property with a null value.

Tombstone events are used by Apache Kafka to remove all previous records related to that row in a process called log compaction. Log compaction helps Kafka reduce the size of each topic while still retaining enough information to replicate the table's current state.

Since tombstone events are used for Kafka’s log compaction, the Willow Adapter ignores them when transforming Debezium events to Redis key-value pairs.

No Primary Key

A table's primary key is a column that contains a unique, not null value and uniquely identifies a single row. For tables with no primary keys, events have null keys.

In this situation, Willow is opinionated and prevents tables without primary keys from being replicated. Willow’s UI does not show tables without a primary key as an option when selecting tables to replicate. Without a primary key, it is difficult to determine which Redis key-value pair should be created, updated or deleted.

The tradeoff of this decision is that Willow cannot be used for tables without a primary key. While these types of tables are sometimes used for containing message logs, their usage is infrequent when following good database design, and their contents are not typically desirable to replicate in a cache.

Composite Primary Key

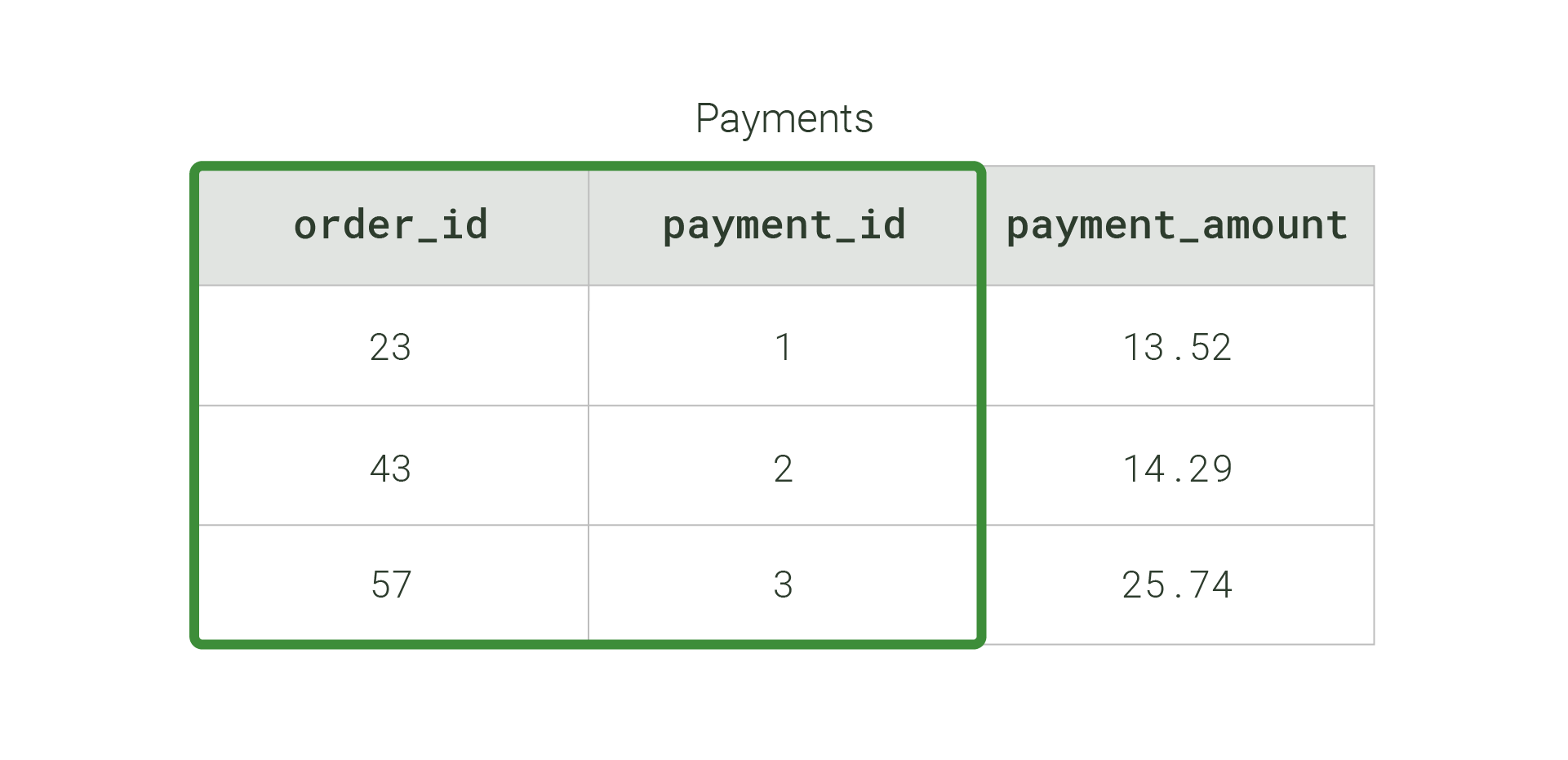

Instead of using a single column as the primary key, a table can use the combination of two or more columns to uniquely identify each row. This combination of columns is called a composite primary key.

In the visual below, the combination of the order_id and payment_id columns is the composite primary key for the Payments table.

order_id and payment_id columns (boxed in green).For tables with a composite primary key, event keys contain information about all column values contributing to the row’s composite key.

Willow supports usage of composite primary keys by joining the individual values with a dot when creating the key for Redis' key-value pair, such as database.table.keyvalue1.keyvalue2.

Conclusion and Future Work

To conclude, Willow is an open-source, self-hosted event-driven framework with a specific use case. It utilizes log-based change data capture to build event streaming pipelines, capturing row-level changes from databases and updating caches in near real-time. It solves a specific form of the cache consistency problem and bypasses various existing solutions, such as TTL and polling. With its simple and intuitive UI, as well as the ability to select which tables and columns to capture, Willow fills a niche in the cache invalidation solution space.

While we are happy with Willow, there is room for improvement. The following are areas where we would like to expand upon in the future.

Decoupling Source and Sink Connectors

In our current architecture, pipelines have a one-to-one relationship with a source database and a sink cache. That is, when a user wants to create a pipeline, they must enter information for some source database and sink cache, even if that information has already been entered for another Willow pipeline. In the enterprise solutions we’ve seen, source connector information can be registered without only being used for a single pipeline; one can specify a source connector that can then be used for multiple pipelines. The same holds for sink connectors.

Decoupling source and sink connectors would also enable Willow to stream changes to different caches without needing to establish new pipelines. Currently for each Willow pipeline, there is one source connector and one sink connector. In certain situations, users may want to stream changes from one source database to multiple Redis caches. To do so, for each additional cache, a user would need to create a new pipeline. However, this is not an ideal design, as each additional pipeline creates redundant Kafka topics, taking up additional disk space. By decoupling source and sink connectors, Willow users could simply tie multiple Redis sinks to the same source database in one pipeline. This would grant users more flexibility and be a more efficient use of resources.

Deployment and Management

Another feature we would like to enable is automatic deployment and management across distributed servers. Currently, Willow operates as a multi-container application on one server. While users can deploy Willow on multiple servers themselves, it would be valuable to have Willow provide that capability by default. This option would make Willow more easily available and fault-tolerant in case a container breaks. We would look into container orchestration tools like Kubernetes or Docker Swarm to implement this feature.

Observability

Currently, there are no observability metrics for monitoring the health and status of Willow’s pipelines. Apache Kafka, Apache Zookeeper, and Kafka Connect all enable Java Management Extensions (JMX), which are technologies that monitor and manage Java applications. Setting up JMX would provide metrics on various groups within the Willow architecture, including Kafka brokers, Zookeeper controllers, and Kafka consumers. Furthermore, in addition to JMX metrics, Debezium connectors provide ways to set up additional monitoring. These primarily provide snapshot and streaming metrics. Adding observability features would allow Willow’s end-users to be better informed and more easily identify issues.

Other ideas

Other features we would like to add include:

- The ability to connect more types of sources and sinks. Currently, Willow only captures changes from PostgreSQL databases into Redis caches.

- The option to encrypt certain steps in the pipeline. For example, while we currently set up Debezium to prefer to use an encrypted connection to the source database, if no certifications are provided, Debezium can default to an unencrypted connection.

- Adding more Redis types. Currently, rows are stored as Redis JSON types within the cache. While we believe this offers the most flexibility, allowing users to store as other types (Redis Hashes, Strings) can be beneficial.

References

- Amazon Found Every 100ms of Latency Cost them 1% in Sales

- Google Study on Website Performance

- How Slow Queries Hurt Your Business

- Cache Strategies

- Cache Invalidation

- What is Change Data Capture

- How Fast is Real-Time?

- Change Data Capture Methods

- Debezium

- Apache Kafka

- PostgreSQL

- PostgreSQL Replication Slots

- Minimum Privileged User Permissions

- Tombstone Events

- Primary Keys

- Usage of Tables with No Primary Keys